Introduction

Currently, health information is available in various formats and through all kinds of media: printed matter such as brochures or flyers, audiovisual formats such as videos, CDs, DVDs, and also CD-ROMs or websites via the Internet.

In most cases, the products and services also differ in their length (scope), which should be based on what information is relevant for decisions and therefore has to be communicated. When selecting the format, orientation towards the objective of the health information and towards its target group plays an important role.

The heterogeneous target groups have different needs. To take these into consideration, special – interactive – information formats were developed. These formats offer personalized or individualized information, where the preferences of the user can be embedded using interactive elements. What the interactive formats have in common is that they all aim to convey the content in a demand-oriented manner using various media and forms of communication. The users are able to control the amount of information and can select the contents they require. Interactive formats have the potential to support inclusion and learning in an active way because the presentation/communication of the contents takes the respective preferences and needs of each individual user into consideration (1).

Examples of interactive elements:

- Games (e.g. in the case of cancer therapy for adolescents: destroy cells that have mutated in different levels and collect shields offering protection from the frequent side effects of chemotherapy (2, 3)

- Questions of knowledge and understanding the theme (with/without feedback; perhaps with the tip to re-read the paragraph) (4, 5)

- Input boxes for e.g. age, gender, risk factors etc. for generating personalized health information (6)

These interactive elements can be used singly or in combination for health information. They are integrated particularly in computer- and Internet-based offers but can also be found in printed material.

Film sequences, texts read aloud, dynamic graphics and real-time contacts (chats with experts, affected people) that are embedded in information offers do not count to the interactive elements here.

Apart from interactive elements, so-called drug facts boxes are being used increasingly for health information.

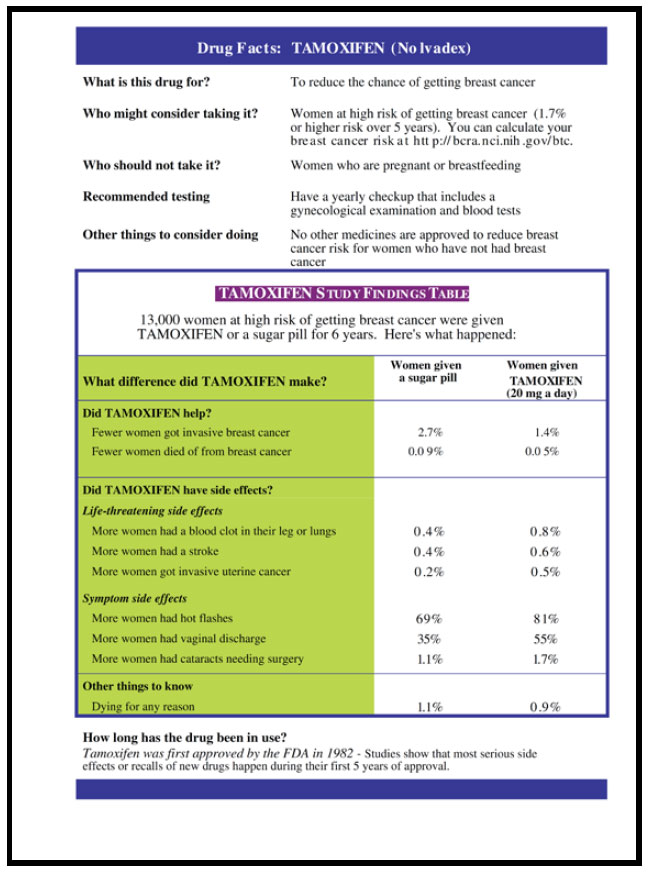

A drug facts box is a one-page, compact, tabular presentation of the benefits and harm of a therapy. The numerical or percentage of frequencies of the main aspects of benefits and side effects for patients undergoing an appropriate therapy are presented along with a corresponding comparison group of patients who either received no therapy or a different one. In addition, the drug facts box can be supplemented with further details, e.g. information about medication, or warnings (cf. Figure 2).

The drug facts box was developed in order to present the benefits and side effects of medication understandably and without distortion (7, 8). The information on the comparison group shows how the disease might progress if untreated or by using another therapy. The principle of the facts box can also be applied to non-drug measures.

Facts boxes can also be used in the process of shared decision-making by physicians and patients. They help the physician to communicate the benefits and harm of a therapy appropriately and to find out the patient’s preferences (9).