1.1. Reason for the choice of the guideline theme

Content is not yet available.

1.2. Objective

The project Development of a guideline for developing evidence-based health information is intended to help improve the quality of health information.

1.3. Field of application

The guideline evidence-based health information is addressed to those who develop and prepare health information. The health information target group (users) is not restricted to specific indications or age groups. A gender-specific differentiation of health information could not yet be put into practice in the guideline. At the moment, it is uncertain whether there are any gender-specific differentiations here. The guideline is applicable for all areas of health.

1.4. Methodological approach

The methodological planning for the guideline evidence-based health information was based on the guideline manual written by the Working Group of Scientific Associations (AWMF) and the ÄZQ for the Development of S3 Guidelines (1), the Guideline Developer’s Handbook by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) (22) and the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE) II instrument (23). Furthermore, proposals for reforming the development of guidelines to further reduce bias in guidelines were taken into consideration (24-30). The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) method was used to evaluate the evidence and the classifications of the recommendations (31).

The Guideline Development Group (GDG) is composed of a heterogeneous group of developers of health information. The Coordination Group (CG) encompasses methodologists in the field of evidence-based medicine at the universities of Hamburg and Halle-Wittenberg. Representatives of the patients and users were included directly in the process of compiling the guideline.

Preparation

No relevant guidelines for the development of health information were found during a systematic research. However, national and international manuals were identified that did address this theme (32-34).

Research, selection and critical evaluation of the evidence

Key questions on content, presentation and the process of creating health information were formulated and agreed upon by the GDG, supported by appropriate questions. In addition, relevant outcomes were defined, structured hierarchically according to GRADE and then endorsed (35). The cognitive outcomes risk perception, comprehension and knowledge were rated as being decisive; comprehensibility and legibility were important but not decisive. The affective outcomes acceptance, attractiveness and trustworthiness or plausibility are of less importance. In coordination with GDG, additional outcomes for individual issues were included in the development process.

Methodologists from the University of Hamburg processed the evidence. Systematic literature researches were carried out based on the key questions and the methodological quality of the individual studies included was assessed by means of standard checklists. An abstract was made of each study (study fact sheet (SFS)). Evidence tables were used to present the evidence for a question across all the included studies and to give a descriptive summary of the effects of each outcome. Effects are only mentioned if a statistically significant difference was indicated. Meta-analyses were not calculated because the interventions examined were complex interventions.

The evidence tables also contain a detailed quality assessment. The quality of the evidence was assessed as very low, low, average or high. The assessment criteria were the design and quality of the included studies, the precision and consistence of the results and the directness of the evidence (36).

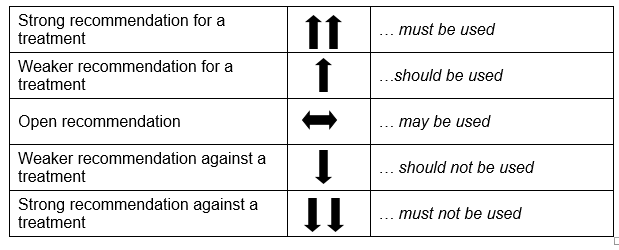

Based on the evidence, recommendations were prepared. A fifth, open recommendation was added to the planned four recommendation strengths: strong and weak, for or against a measure. The following formulations were used (see Table 1).

Tabelle 1: Recommendation strengths

When selecting the strength of recommendation, the quality of the evidence, the degree and exactness of the effects, and the significance of the outcomes were given particular consideration. The recommendations were discussed and agreed upon by the members of the GDG. Issues concerning ethical requirements, for instance the content requirements, were approved as obligatory components of health information without the processing of evidence.

When selecting the strength of recommendation, the quality of the evidence, the degree and exactness of the effects, and the significance of the outcomes were given particular consideration. The recommendations were discussed and agreed upon by the members of the GDG. Issues concerning ethical requirements, for instance the content requirements, were approved as obligatory components of health information without the processing of evidence.

A detailed description of the methodological procedure can be found in the methodreport (37).

1.5. Consultation and Approval

Following the preparation of the recommendations and texts, a public consultation period of the guideline was commenced. The preliminary guideline was publicly accessible over its own Internet page from 10.10.2016 to 30.11.2016 (37). The methodology and the results of the evaluation procedure are documented in the guideline report. Following the consultation period, the guideline was reviewed by the CG and again presented to the GDG. On 13.02.2017, the amended guideline was agreed upon by the GDG in an Adobe Connect Conference.

1.6. Editorial Independence

Guideline funding

The University of Hamburg provided the staff resources. The members of the GDG participated in the development process during the course of their duties. The material resources were financed by the Techniker Krankenkasse’s Scientific Institute for Use and Efficacy in Health Care (WINEG).

Disclosure and handling of potential conflicts of interest

At the beginning of the project, the members of the GDG used a standard form to disclose any possible conflicts of interest. The declaration referred to possible financial, commercial and immaterial interests. The declarations from the GDG members were updated before approval and documented in the guideline report.

1.7. Validity duration and Updating procedure

So far, the reminder system in the data bases has been used for updating. Any new relevant literature is passed on to the GDG. A complete revision of the guideline should be done after four years at the latest.

However, the aim is to develop a methodical procedure that enables the guideline to be updated within shorter periods or to adapt it continuously to current developments. For this, a working group is to be set up by the section patient information and participation of the DNEbM, which will develop an outline of methods and deal with issues concerning responsibility and funding.

1.8. Outlook

The guideline is to be implemented using a scientifically supervised training program, which contains two modules and will take a total of five days.

The first module, an EbM Training Module, consists of five sub-modules on the methods of evidence-based medicine (cohort studies and randomized-controlled studies, questions and literature searches, systematic reviews, diagnostic tests and evidence-based health information). The second module is about how to use the guideline.

It is intended to check the efficacy of the guideline and the training program in a randomized-controlled study to determine the extent to which the recommendations of the guidelines have been put into practice. Before this, pilot tests will be carried out in the target group of the creators of health information and the training program will be monitored with regard to comprehensibility, feasibility and acceptance and, if necessary, optimized. In addition, the need for supplementary materials to improve the usability of the guideline (e.g. online glossary, summary of recommendations, brief guide on systematic literature research) will be identified.